The growl of the cheetah once echoed across the country except for the high mountains, coastal areas and the northeast. They are the only predator to have perished since India’s independence in 1947. Recently, eight large cats from Namibia flew in a chartered cargo flight to the northern Indian city of Gwalior in 2022, as part of an ambitious and contentious plan for the reintroduction of cheetahs in India after a seven-decade absence. They were then relocated to their new habitat, a large national park in the centre of India, where scientists aim to reintroduce the world’s fastest land animal.

The best way to travel to see the relocated cheetahs is by booking a car rental in Gwalior to the national park. The fastest terrestrial animal on the planet is ready to make a triumphant return to Indian fauna. But do the Indians of today know why it vanished from India in the first place?

Table of contents

The history of cheetahs in India

Cheetahs in India – from mythology to neolithic paintings

The cheetah is not unfamiliar in India. The country was once the final point in the arc of its range extending to Iran and Africa. The very word ‘Cheetah’ is of Sanskrit origin meaning ‘variegated’, ‘adorned’ or ‘painted’. The sacred Durga Saptashati mentions the cheetah as Goddess Durga’s vehicle, symbolizing grace, strength, agility, and enormous power, thus associating the cheetah with grandeur, strength, beauty, and ferocity. Additionally, the cheetah has been traditionally used as a symbol of bravery and valor.

The cheetah’s religious significance in the Vedas and its association with Lord Shiva, who is believed to wear its skin, suggest its importance in ancient India. Furthermore, cave paintings from the Neolithic period found in Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh depict the cheetah, indicating its presence in India since ancient times. Cheetahs were known for their courageous prowling across the country, particularly in Central India. But what caused its extinction in the country?

The extinction of cheetahs in India

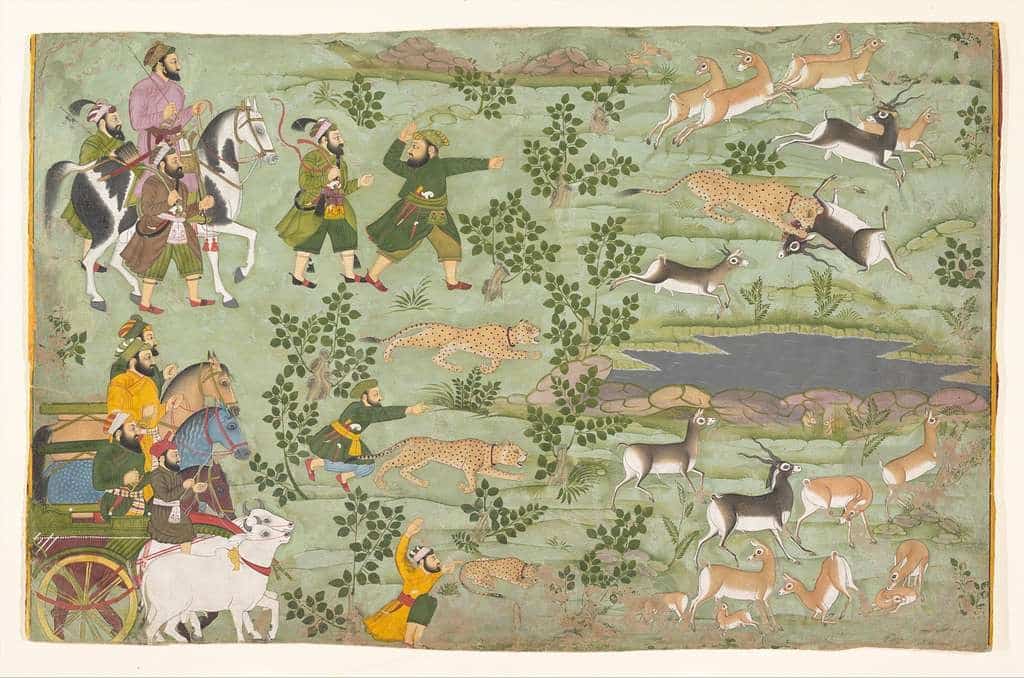

Cheetahs were frequently documented throughout the Mughal period. Hunting with cheetahs was one of the Mughals’ most popular pastimes, if not the ultimate regal sport. Mughals and aristocrats both admired cheetahs. As a result, a network emerged to capture and deliver cheetahs to the royals. King and nobles domesticated them and used them for coursing and hunting. Cheetahs, unlike leopards, were never known to harm humans and were thus simple to tame and train.

Mughal emperor Akbar, who reigned from 1556 to 1605, owned 1,000 cheetahs. The animals were utilised for blackbuck and gazelle hunting. Jahangir, Akbar’s son, is claimed to have caught almost 400 antelopes via cheetah coursing. India was the first country in the world to raise cheetahs in captivity during the reign of Emperor Jahangir in the 16th century. Cheetah populations have declined due to capture for hunting and the difficulty of breeding the animals in captivity. According to records, during the 19th century, the number of cheetahs had dropped from 10,000 during Akbar’s reign to a few hundred.

By the time the British arrived in India, the Asiatic cheetah population had already begun to dwindle.

During British control, hunters viewed giant cats like lions and tigers as challenging games to shoot, but they regarded smaller animals like cheetahs as “vermin to be slaughtered” because they obstructed hunting. Consequently, hunters exterminated cheetahs in large numbers because the animals would infiltrate cities and kill cattle.

The colonial authority also hunted cheetahs in huge numbers, with incentives ranging from Rs 6 for pups to Rs 18 for an adult. Between 1870 and 1925, an average of 1.2 cheetahs were murdered for prizes per year. Bounty-hunting may have hastened, if not caused, its extinction in many areas where it still existed. The British hunts also prompted Indian princely nations to hunt them, which were already hunting larger cats like tigers. Cheetahs were already becoming scarce in the nineteenth century, and even more so in the twentieth.

It is thought that the last Indian cheetahs died in 1947. The last three Indian cheetahs are reported to have been slain in 1947 by Maharaja Ramanuj Pratap Singh Deo of Koriya in present-day Madhya Pradesh. In 1952, they were legally declared extinct. Since the country’s independence from British domination, the cheetah is the only big mammal to have become extinct.

Homecoming of cheetahs in India

The great return to the wild

The proposal for the reintroduction of cheetahs in India has been in the works for decades. The Indian government first approached Iran, where the Asiatic cheetah, the same subspecies that became extinct in India, still exists, and was even interested in cloning the species. When Iran refused repeatedly, citing a lack of the species in its own country, the Indian government turned to the African subspecies.

The national government issued an ‘Action Plan for the Introduction of Cheetah in India’ in January 2022, outlining its relocation plans. Between 2010 and 2012, ten sites were surveyed. The Kuno National Park (KNP) in Madhya Pradesh was deemed fit for cheetahs with the fewest management interventions since significant investments were made in this protected region to reintroduce Asiatic lions, another endangered species.

In July 2022, India struck an agreement with Namibia for the reintroduction of cheetahs in India. Eight cheetahs — five females and four males — took off from Namibia’s capital Windhoek on September 16 and arrived at Jaipur airport on September 17, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s birthday. The eight cheetahs were flown from Hosea Kutako International Airport in Windhoek, Namibia’s capital, to Gwalior, around 200 kilometres from Sheopur. Additionally, the aircraft was originally scheduled to land at Jaipur, but this was later modified to Gwalior.

Kuno national park also offers plenty of natural cheetah habitats, including grasslands, savannahs, and open woodland with evergreen riverine ravines. Kuno is located in the Sheopur district, which features rainfall, temperatures, altitude, and other variables comparable to those found in South Africa and Namibia. Moreover, for the animals to quarantine before being released into the wild, an electrified enclosure with ten sections of varying sizes has been created.

Each cheetah is assigned a dedicated team of volunteers who watch and track the animal’s movements. Each cheetah has a satellite radio collar that provides geolocation updates. According to official authorities, the cheetahs, five females and three males are adjusting well to their new surroundings. They had adapted to India’s climate far better than planned and had subsequently killed multiple blue bulls, sambar, and cheetals.

Environment Minister Bhupender Yadav said that “the aim behind the translocation is not only the reintroduction of cheetahs in India, but also to develop a cheetah meta-population that will help in the global conservation of the animal.”

Recently, Kuno National Park has reported the arrival of its first litter of Cheetah cubs, and they are said to be in good health. The four cubs were born to Siyaya, one of the Namibian cheetahs. The park welcoming its first set of baby cheetahs as part of Project Cheetah is fantastic news for the conservation of cheetahs in India. It indicates that the project is progressing well and is successfully breeding cheetahs in the park.

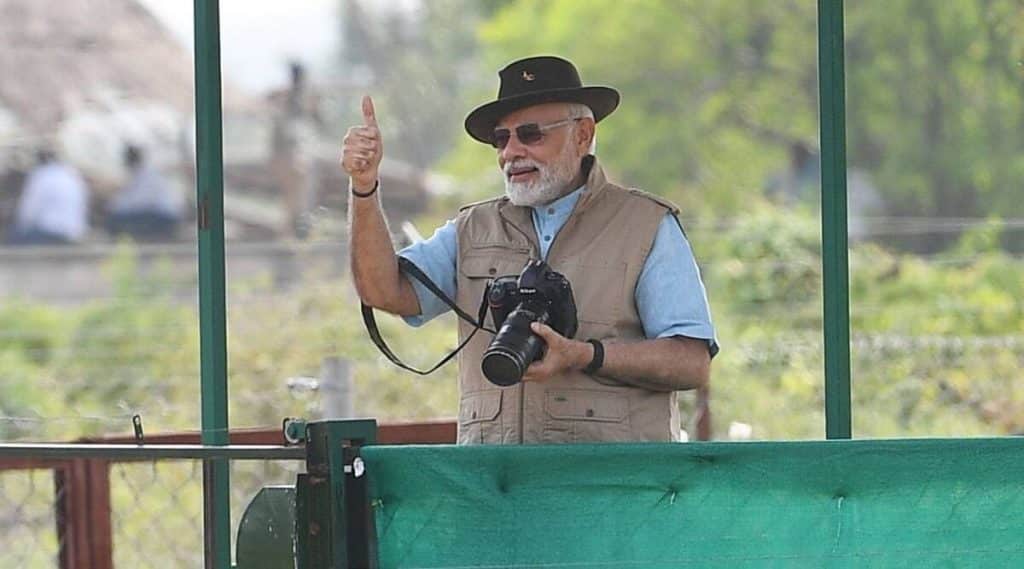

How PM Modi saw it as an opportunity to conserve wildlife

On September 17, 2022, Prime Minister Narendra Modi released eight cheetahs brought from Namibia in Kuno National Park in Sheopur. The PM compared the cheetah sprint to India’s development race in ‘Azadi Ka Amritkaal,’ or the 75th year of independence. As per his claims, reintroducing Cheetahs to India will aid in the restoration of open forest and grassland ecosystems, as well as improve livelihood prospects for the local community.

MP Modi also stated that it will promote biodiversity, as well as eco-tourism and job prospects in the region. He described Project Cheetah as an effort to conserve the environment and wildlife. He called one of the cheetahs “Asha,” which means “hope”.

On a precautionary note, the Prime Minister asked “all citizens” to be “patient” and wait a few months before visiting the park to witness the cheetahs. “Today, these cheetahs have arrived as visitors and are unfamiliar with the location. We need to give these cheetahs a few months to settle in Kuno National Park. India is observing international guidelines and taking all possible measures to reintroduce cheetahs into the country. “We must not let our efforts fail,” the Prime Minister added.

The challenges with the reintroduction of cheetahs in India

The mission is not without risks. Some are concerned that relocating animals is usually laden with danger, and that releasing the cheetahs into a park may put them in danger. Cheetahs are fragile animals who shun fighting and are preyed upon by other predators. In addition, Kuno Park has a large leopard population that could harm cheetah cubs.

Officials also say that cheetahs are highly adaptable creatures and that they have thoroughly investigated the nominated site for habitat, prey, and the potential for man-animal conflict. Despite concerns that the cheetahs might escape and be killed by humans or other animals, officials insist that these fears are baseless.

How can the reintroduction of cheetahs in India benefit Indian tourism?

The reintroduction of cheetahs project in India is projected to generate new opportunities for locals as tourist numbers increase dramatically. The presence of cheetahs in the national park would increase tourist traffic and improve visitor amenities in the Sheopur district and surrounding areas. In Sheopur, a hotel is also being built under the franchise of the MP Tourism Board. It will also promote Wildlife tourism in India.

Aside from people working in the hospitality business, the reintroduction of cheetahs project in India will benefit communities such as Morawan, Sesaipura, Tiktoli, Adwada, Hathedi, and Chakrana. Shivraj Singh Chouhan, Chief Minister of Madhya Pradesh, has proposed the establishment of five skill camps where people will be trained for jobs in the hospitality industry.

Travel guide – Kuno National Park

Kuno National Park is in the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh. In 1981, authorities established this park as a wildlife sanctuary, covering a total area of 344.686 square kilometres in the districts of Sheopur and Morena. The park received national park status in 2018, and it is located in the northern district of Sheopur, at the heart of the Vindhya range. The park is dominated by grasslands similar to African savannas and scant woods. Historically, kings used this park as a hunting field.

The sanctuary receives its name from the Kuno River, which flows through it from south to north and serves as the forest’s lifeline. Situated between the Aravallis and the Madhav National Park, Kuno also serves as an important wildlife corridor.

The flora in Kuno National Park

Kuno boasts one of the most unusual combinations of woodland and vegetation in Madhya Pradesh and the surrounding areas. The forest area of Kuno National Park is mostly dominated by Kardhai, Salai, and Khair trees among predominantly mixed woods, which contributes to the park’s diverse flora and wildlife. Kuno National Park contains 123 types of trees, 71 kinds of shrubs, 32 species of climbers and exotic species, and 34 species of bamboo and grasses.

The fauna in Kuno National Park

Kuno National Park has a diverse ecosystem with 33 species of mammals, 206 species of birds, 14 species of fishes, 33 species of reptiles, and 10 species of amphibians. With so many faunal species, it is one of the most biodiverse places in the Central Indian landscape.

The following are the main fauna species of general tourist interest in Kuno National Park:

- Spotted deer or Chital (Axis axis)

- Sambar (Cervus unicolor)

- Barking deer or Indian Muntjac (Muntiacus muntjak)

- Chousingha or Four-horned antelope (Tetracerus quadricornis)

- Nilgai or Blue bull (Boselaphus tragocamelus)

- Indian Gazelle or Chinkara (Gazella gazella)

- Black buck (Antilope cervicapra)

- Gaur or Indian Bison (Bos gaurus)

- Leopard (Panthera pardus)

- Wild dog or Dhole (Cuonal pinus)

- Striped Hyaena (Hyaena hyaena)

- Indian Wolf (Canis lupus)

- Jackal (Canis aureus)

- Wild boar (Sus scrofa)

- Sloth bear (Melursus ursinus)

- Indian fox (Vulpes bengalensis)

- Jungle cat (Felius chaus)

- Desert cat (Felin sylvestris)

- Common palm civet (Paradoxurus hermaphroditus)

- Small Indian civet (Viverricula indica)

- Grey mongoose (Herpestes edwardsii)

- Small Indian mongoose (Herpestes javanicus)

- Ruddy mongoose (Herpestes smithii)

- Indian hare (Lepus nigricollis)

- Indian porcupine (Hystrix indica)

- Indian gerbil (Tatera indica)

- Indian tree shrew (Tupaia belangeri)

- Hanuman langur/Common langur (Presbytis entellus)

- Rhesus monkey (Macaque mulata)

Kuno National Park safari

Safari in Kuno National Park is one of the most popular activities. Safari rides are provided in the morning and evening. To get the most sightings, we recommend that you use both of these options. You can reserve safari rides either at the park’s ticket desk or online. The bookings for a month start approximately a month earlier. All bookings open at 11 AM.

Kuno National Park safari timings

- Morning – 6:00 AM to 9:30 AM

- Evening – 4:00 PM to 6:00 PM.

Kuno National Park safari ticket price

Here are the complete details regarding the ticket price of the Kuno National Park –

- Park Safari Ticket Price – 750/- per person

- Service fees – 30/- Per Booking

Besides the official safari rides, private vehicles are also allowed for the sighting of animals. There is a forest permit fee per gypsy/vehicle and additional charges for hiring a guide. The recommended speed while driving is 20 km/hr.

Best time to visit Kuno National Park

Except during the monsoon season, Kuno National Park is open to visitors all year (1st July to 15th October). However, because the park is in a tropical position and has unique vegetation and physical characteristics, the best time to visit Kuno is from October to March, when the weather is excellent.

How to reach Kuno National Park

By Air: The nearest airport to Kuno National Park is Gwalior Airport, which is 175 kilometres away. All of India’s main cities are well-connected to this airport.

By Rail: The nearest train station to Kuno National Park is Gwalior Railway Station, which is 175 kilometres away. There are numerous taxis accessible from here that will transport you to Kuno National Park.

By Road: Kuno National Park is 175 kilometres away from Gwalior. You can book a cab to the national park from Gwalior and enjoy the picturesque splendour of the area as you get closer to your destination.

What will happen in the future?

According to experts, re-arrangement of cheetahs in India will be considered after the population reaches 500. To fulfil this goal, South Africa and Namibia will send 8 to 12 cheetahs to India each year. Aside from that, the genealogy of cheetahs in India will also be involved in this. If all goes as planned, Kuno will be home to four big cats: lions, tigers, cheetahs, and leopards. But can these species coexist peacefully in the same environment? This has never happened before anywhere else.

The reintroduction of cheetahs in India will benefit wildlife tourism, but it may also endanger inter-species and human-animal conflict. Preparations are in full swing, as the authorities expect cheetah tourism to be possible by February 2023. Soak in all the wilderness by booking a car rental to take you to Kuno National Park with a local driver. Install Savaari cab booking app for offers and discounts on outstation rentals.

Useful links:

- India to release five more cheetahs into Kuno National Park

- Information related to Kuno National Park

- Kuno National Park safari booking

- 12 cheetahs released in acclimatisation enclosure at Kuno National Park after two-month quarantine

- Boost to India’s wildlife diversity: PM Modi on 12 cheetahs arriving in M.P.’s Kuno National Park

- Forest dept looks to check poaching threat before cheetah release in Madhya Pradesh

- 5 cheetahs from South Africa to be released into the wild in Madhya Pradesh

- Cheetahs seen in the wild in India after 70 years at Kuno National Park

Last Updated on January 17, 2024 by Swati Deol